When we think about skincare, most of us go straight to products. We obsess over finding the right serum, the perfect cleanser, or moisturizer everyone on TikTok is raving about (like beef tallow…). But here’s something we often overlook: the water coming out of your faucet. Yes, your water. The truth is, your water might be quietly sabotaging your skin, and the effects can be dangerous, varying depending on where you live.

Well, why is this?

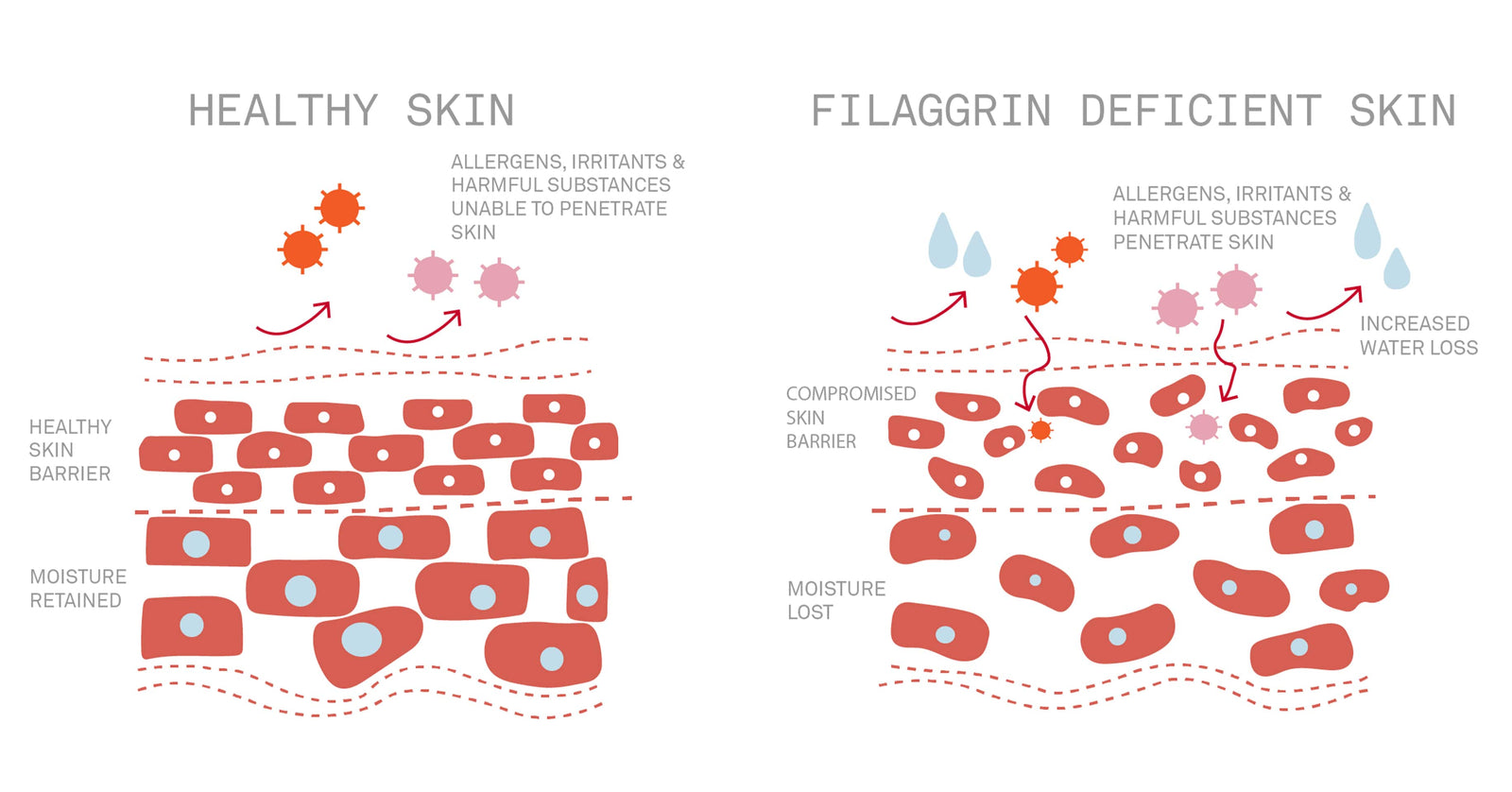

Hard water. It’s basically water that has a high mineral content, usually calcium and magnesium. On your skin, they can do more harm than good. If you combine hard water with your soap or cleanser, it doesn’t rinse off as well. Instead, it leaves behind this soapy/slimy residue that can clog pores and cause your skin to feel tight or dry. In the long term, that gunk interferes with your skin barrier. If you have conditions like eczema or acne, that interference can totally make flare-ups even worse. Additionally, leftover minerals can even interfere with the active ingredients in your products, making them less effective. Think of it like trying to spread lotion over sandpaper—your skin just can’t absorb things the same way.

One quick way I check for hard water is by noticing how products lather. As you rub your cleanser, or even hand soap, and you notice it feels slimy in your hands and doesn’t foam as well as it usually does, that’s a sign the water might be hard. And if you ever travel and suddenly notice your skin acting up, it’s worth checking the local water hardness through a quick Google search. Here’s a handy chart illustrating water pressures across states in the US.

Now here’s where the conversation gets bigger than just skincare tips. Water quality and access are not the same everywhere. Hard water is more common in certain geographic regions, but it’s also more likely to affect communities with aging or underfunded infrastructure. In some poor neighborhoods, individuals just can’t afford to equip their homes with water softeners or quality shower filters that wealthier communities take for granted. Even in the same city, plumbing and maintenance variations may lead to some households receiving consistently harsher water than others.

For individuals of color, these issues are even bigger. Eczema, hyperpigmentation, or scalp problems might not appear the same on darker skin, so they’re dismissed or treated improperly. Add hard water to the mix—exacerbating dryness and redness—and it’s even worse. But still, you never really hear water quality discussed in skincare advice or even in dermatology recommendations. This silence shows that the larger environmental and systemic issues impacting marginalized groups tend to get swept under the rug in health discussions.

So what can you do if you feel your water is part of the solution? The good news is that several low-cost measures can help. Shower filters will reduce mineral content and although some models are expensive, there are cheaper ones that work. For people who have very sensitive skin, applying a rinse with micellar water or even a splash of distilled water makes the residue more loosenable. Selecting gentle, pH-balanced cleansers (and not foamy ones) also makes your skin less susceptible to the harsh effects of hard water. And something easy everyone can do: apply moisturizer as soon as possible after showering to trap in the moisture before minerals and evaporation dry out your skin. The best choice in the long term would ultimately be to install a water softener system in your whole house, but those are quite expensive, costing thousands.

The bottom line? Skincare isn’t just about your products. Fresh, skin-friendly water should be the standard for all people, no matter where they live. But now it’s a luxury. Our products do matter a lot—yes. But so do the subtle environmental factors that influence our skin health every night. By learning how something as prevalent as water pressure or mineral levels impacts us, not only do we better care for our own skin, but we come to realize why having access to healthy, safe water is a matter of equity, not a luxury.

How is your water?

References

H₂O Distributors. Hard-Water Map. H₂O Distributors, n.d., https://www.h2odistributors.com/info/hard-water-map/. Accessed 24 Aug. 2025.

U.S. Geological Survey. Hardness of Water. Water Science School, U.S. Geological Survey, n.d., https://www.usgs.gov/water-science-school/science/hardness-water. Accessed 24 Aug. 2025.

Roland, James. “Hard Water vs. Soft Water: Which One Is Healthier?” Healthline, reviewed by J. Keith Fisher, MD, 30 July 2019, https://www.healthline.com/health/hard-water-and-soft-water. Accessed 24 Aug. 2025.