Ringworm, or it’s professional name, “tinea corporis,” is one of the most common fungal skin conditions in the world! Interestingly, ~25% of the population worldwide is expected to experience ringworm at some point during their life…

If you look up “ringworm” online, you’ll notice that a lot of the images show light skin. And in all those images, ringworm symptoms manifest as a bright red, circular patch.

In this article, we’ll explore what the internet fails to show us: how ringworm looks on darker skin tones.

So first, what causes ringworm?

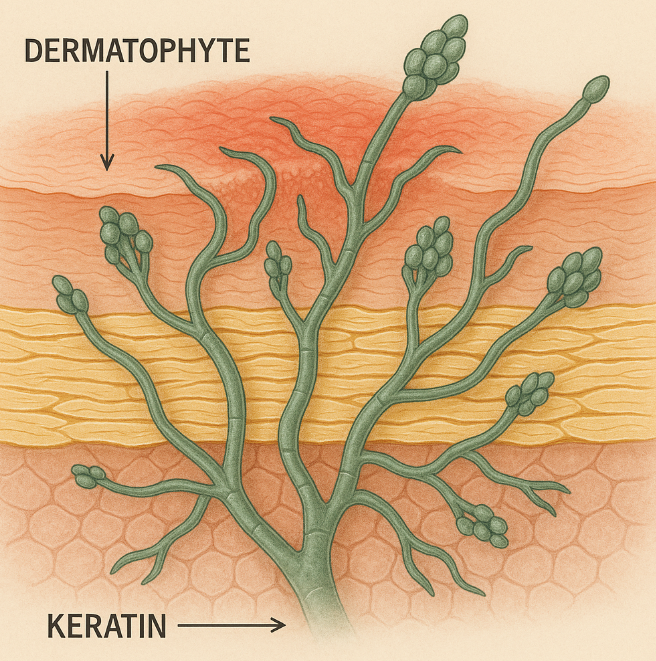

Shockingly, it’s not caused by a worm. Well, ringworm is a fungal infection, meaning that it is contagious (like direct skin contact) and caused by a fungi. Specifically, ringworm is caused by the group of fungi called dermatophytes.

Unfortunately, dermatophytes can be found almost anywhere. Like most fungi, they love warm, humid environments like locker rooms and saunas. To avoid ringworm, be sure to stay clean, washing your hands/body thoroughly!

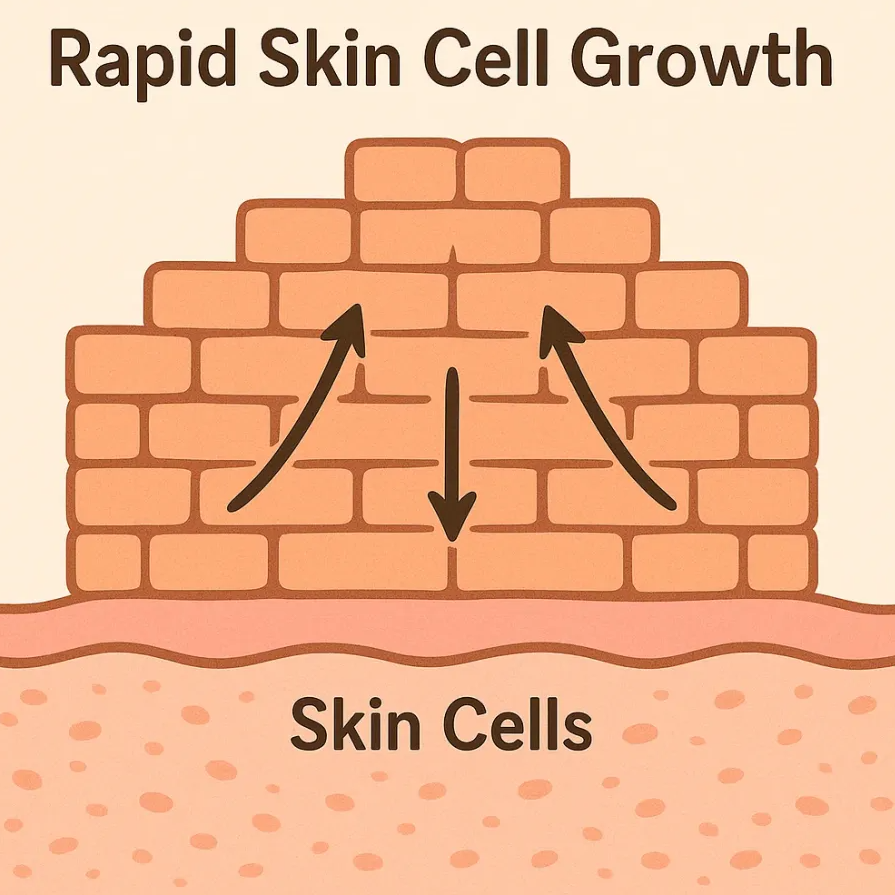

Back to the skin. These rascals feed on a crucial protective protein on your skin, hair, and nails, called keratin. As they digest keratin, they invade and irritate the outer layer (epidermis) of your skin, triggering inflammation. This then leads to ringworm, characterized by itchy, circular patches.

Why does ringworm look red on lighter skin?

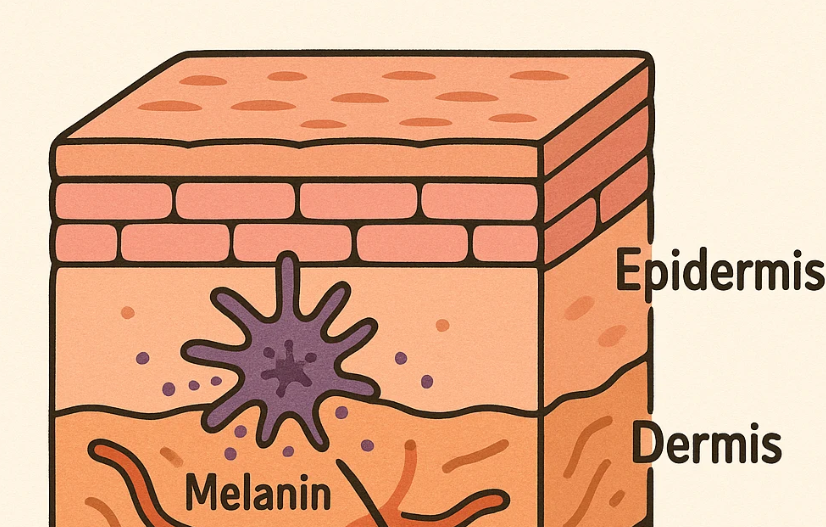

On lighter skin tones, inflammation typically shows up as a clear, visible redness. So when these dermatophytes feed on keratin, the inflammatory response will kick in, increasing blood flow to the area. Which, naturally, will appear more red in color since lighter skin contains less melanin.

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4560-ringworm

But…what about darker skin?

Since darker skin will have more melanin (the pigment that gives skin its color), inflammation doesn’t typically appear as red like lighter skin. Instead, the inrceased melanin can mask the inflammation, making it look gray, purple, or brown. Also, increased melanin can make the “border” of the rash can appear subtler on darker skin tones. For these reasons, ringworm rashes might be harder to spot on darker skin, or might look like a totally different condition.

✅Identifying a ringworm lesion on darker skin—a checklist

Shape: Does it form a circular, ring-like patch with a clearer center?

Texture: Are the edges slightly raised/scaly?

Color: Is the lesion gray, brown, or purplish instead of red?

Itchiness: Is it often itchy? Especially around the border of the lesion?

Note: don’t rely on this checklist for medical advice! I’m no expert… Also, ringworm is often confused with inflammatory conditions like psoriasis and eczema, so be wary of that.

Spread: Is the rash growing outwards over time?

Takeaway

Knowing what ringworm actually looks like on everyone can help us close this representation gap, allowing everyone to receive the treatment they deserve. It means faster and more accurate diagnoses. Plus, it reminds us that medical info and pictures should show all shades of skin, not just one type.

References

Cleveland Clinic. “Ringworm (Tinea Corporis): What It Looks Like, Causes & Treatment.” Cleveland Clinic, 21 Oct. 2022, my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4560-ringworm. Accessed 20 Oct. 2025. Cleveland Clinic

WebMD. “Ringworm: Causes, Symptoms, Treatments & How to Identify.” WebMD, 19 Dec. 2023, www.webmd.com/skin-problems-and-treatments/what-you-should-know-about-ringworm. Accessed 20 Oct. 2025. WebMD

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Clinical Overview of Ringworm and Fungal Nail Infections.” CDC, 15 July 2024, www.cdc.gov/ringworm/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html. Accessed 20 Oct. 2025.