Recently, with the rapid evolution and integration of artificial intelligence in medicine, I’ve been very interested in AI dermatology tools. I decided to explore whether the datasets used to train AI models adequately reflect darker skin tones. Since this paper aligns closely with the mission of SkinDex, I’m sharing it here to showcase my findings. I think it also adds a valuable academic perspective to this blog’s mission.

Introduction

Skin conditions are among the most common health concerns worldwide, affecting roughly a third of the global population (Kamíński et al.). But for many patients, access to a dermatologist is limited, as they’re often overbooked or scarce—especially in underserved communities. This has given rise to artificial intelligence, offering a more accessible way for patients to diagnose their own conditions. But in dermatology, there has been a recurring and alarming issue: darker skin tones are often underrepresented. Given the prevalence of skin conditions, disparities in diagnostic accuracy across skin tones pose detrimental risks for millions of patients. This raises a critical question: To what extent do dermatology AI diagnostic tools reflect darker skin tones in their training datasets, and how does this representation affect diagnostic accuracy? Extracting from scientific studies and popular sources, the datasets used to train AI diagnostic tools were found to overwhelmingly underrepresent darker skin tones, and in turn, perform disproportionately inaccurately compared to patients with lighter skin tones.

AI Diagnostic Tools

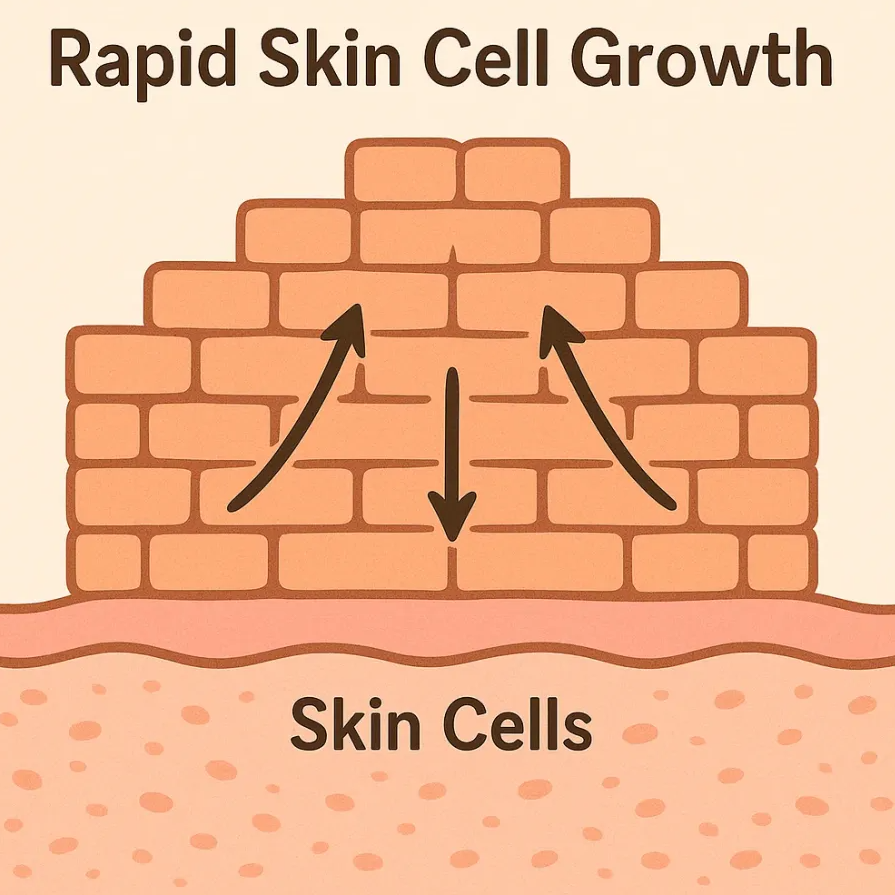

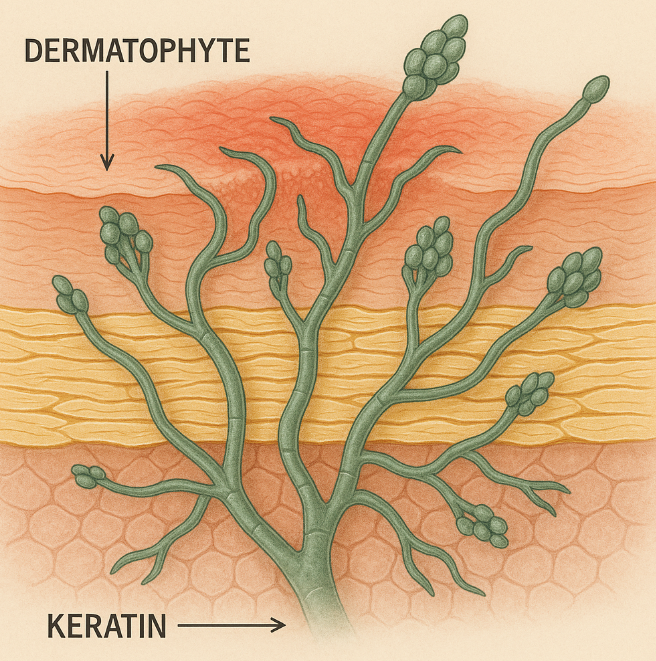

Before exploring racial disparities, it´s important to first understand how AI diagnostic tools function. These algorithms operate using artificial intelligence, often trained on large datasets of annotated images of skin conditions. They can be in the form of tools, apps, or software systems. Using a photographic scanner to analyze a patient´s skin concern, the model then matches the user´s skin condition with a potential diagnosis. These tools have shown great promise in clinical settings. About 12% of dermatologists report using AI assistance in practice (Partridge et al.), and studies note that AI tools can improve diagnosis accuracy up to 60% (Trafton). But an AI model’s performance strongly depends on the datasets it was trained on. Because symptoms on darker skin look very different in color and texture, AI diagnostic tools that are not sufficiently trained to assess darker skin tones may overlook or misinterpret these differences. For underrepresented patients who rely on them, this is deeply endangering, as their conditions may be misdiagnosed or left untreated. In some cases, with conditions like melanoma, a type of skin cancer, could even be deadly. And in dermatology, darker skin tones have historically been underrepresented.

Historical Underrepresentation of Darker Skin Tones in Dermatology

Underrepresentation has long been an issue in medicine. Stanford researchers found that in educational material in dermatology, just 1 in 10 images reflect black/brown skin tones (Myers). As a result, many physicians are left underprepared to treat patients with darker skin tones. This is similarly shown by a study conducted by researchers Louie and Wilke, who analyzed more than 4,000 medical textbook images. They discovered that 74.5% depicted light skin, with merely 4.5% showing darker skin (Louie and Wilke), emphasizing just how prevalent inequitable representation is in medical education. Experts have noted that this disparity isn’t intentional, but rather the result of the systemic gaps in training. As Northwestern professor Matt Groh explains, “Probably no doctor is intending to do worse on any type of person, but it might be the fact that you don’t have all the knowledge and the experience, and therefore on certain groups of people, you might do worse” (Trafton). This helps reveal the underlying causes that have allowed racial disparities to persist in medicine. Understanding this background, it’s important to examine whether AI diagnostic tools exhibit this same representation gap.

Prevalence of Dark Skin Representation in AI Datasets

Research has shown that darker skin tones are severely underrepresented in dermatology AI datasets. In one study conducted by Joerg and colleagues, four popular AI models were prompted to generate images of skin conditions. Across all images, 89.8% were of lighter skin tones, whereas merely 10.2% represented darker skin, revealing a clear imbalance in the datasets these models rely on (Joerg et al). Researchers in another study found a similar pattern as well. In a review of AI training datasets, merely 4.3% of images represented Black or African American skin (Kadam et al.). As evident, this research makes it clear that current AI datasets fail to adequately include images of darker skin tones. Given these disparities in representation, it’s critical to assess how AI diagnostic tools actually perform on patients.

Consequences of Underrepresentation in AI Diagnostic Tools

When used in practice, AI diagnostic tools have been shown to perform drastically less accurately on patients with darker skin tones. According to Kamulegeya and colleagues, one AI model diagnosed conditions with an accuracy of 17% on dark skin compared to 70% on lighter skin (Kamulegeya et al.). This disparity indicates that patients with darker skin are often at a higher risk of misdiagnosis. Across other models and populations, a similar pattern was seen. Police and researchers analyzed the performance of three commonly used AI diagnostic apps on over 30 Indian patients. Diagnostic accuracy ranged from 46.9 to 59.4%, deeming the AI models insufficiently reliable for clinical use—particularly for patients with darker skin tones (Police et al.). Concerningly, the use of AI assistance itself has also been shown to worsen existing diagnostic disparities. Groh and colleagues found that AI assistance “exacerbated the accuracy disparities by primary care physicians by 5 percentage points” when diagnosing patients with darker skin tones (Harris). Their finding suggests that, instead of mitigating the existing inequities in healthcare as intended, AI tools trained on biased datasets place patients with darker skin at a greater risk of misdiagnosis.

Conclusion

The findings of this research strongly highlight an urgent gap: the underrepresentation of darker skin tones in AI training datasets disproportionately reduces diagnostic accuracy for patients with darker skin. Artificial intelligence is fully capable of revolutionizing dermatology. But before AI can be reliably and safely integrated into clinical practice, researchers, developers, and physicians must work together to ensure equitable skin-tone representation in AI datasets. Additionally, further research evaluating the performance of AI diagnostic tools across diverse populations is necessary to help ensure that these disparities don’t persist. A future like this is well within reach. By taking these steps collectively, all patients, no matter their skin tone, can finally receive the care they deserve.

Works Cited

* Aggarwal, Pushkar, and Francis A. Papay. “Artificial Intelligence Image Recognition of Melanoma and Basal Cell Carcinoma in Racially Diverse Populations.” Journal of Dermatological Treatment, vol. 33, no. 4, June 2022, pp. 2257–2262. EBSCOhost, doi-org.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/10.1080/09546634.2021.1944970.

* Benčević, Marin, et al. “Understanding Skin Color Bias in Deep Learning–Based Skin Lesion Segmentation.” Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, vol. 245, 2024, doi.org/10.1016/j.cmpb.2024.108044.

*Dowie, Teniola. “Exploring the Diagnostic Capability of Artificial Intelligence in Dermatology for Darker Skin Tones: A Narrative Review.” Cureus, Oct. 2025, https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.94909.

Harris, Shanice. “Racial Bias Exists in Photo-based Medical Diagnosis Despite AI Help.” Northwestern Now news.northwestern.edu/stories/2024/02/new-study-suggests-racial-bias-exists-in-photo-based-diagnosis-despite-assistance-from-fair-ai.

*Joerg, Lucie, et al. “AI‐generated Dermatologic Images Show Deficient Skin Tone Diversity and Poor Diagnostic Accuracy: An Experimental Study.” Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, July 2025, https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.20849.

Kadam, P., et al. “Evaluating the Diagnostic Accuracy of AI Models in Dermatology: Addressing Skin Tone Bias to Improve Outcomes for Ethnic Skin Types.” Journal of Investigative Dermatology, vol. 145, suppl. 8, Aug. 2025, pp. S209–S210, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jid.2025.06.1488.

*Kamiński, Mikołaj, et al. “‘Dr. Google, What Is That on My Skin?’—Internet Searches Related to Skin Problems: Google Trends Data from 2004 to 2019.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 18, no. 5, 2021, p. 2541, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052541.

*Kamulegeya, L., et al. “Using Artificial Intelligence on Dermatology Conditions in Uganda: A Case for Diversity in Training Data Sets for Machine Learning.” African Health Sciences, vol. 23, no. 2, 2023, pp. 753–763, https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v23i2.86.

*Louie, Patricia, and Rima Wilkes. “Representations of Race and Skin Tone in Medical Textbook Imagery.” Social Science & Medicine, vol. 202, 2018, pp. 38-42, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.02.023.

Merchan, Davi. “Racial Bias in Medical AI Tools Is Impacting Patient Care, These Doctors Have Identified Inclusive Applications – the Plug.” The Plug, 25 May 2022, tpinsights.com/racial-bias-in-medical-ai-tools-is-impacting-patient-care-these-doctors-have-identified-inclusive-applications.

Myers, Andrew. “AI Shows Dermatology Educational Materials Often Lack Darker Skin Tones.” Stanford HAI, Stanford University, 2023, https://hai.stanford.edu/news/ai-shows-dermatology-educational-materials-often-lack-darker-skin-tones

“New AI Dataset Advances Dermatology for Darker Skin Tones.” ReachMD, 2025,

reachmd.com/programs/clinicians-roundtable/new-ai-dataset-advances-dermatology-for-darker-skin-tones/30020/.

*Partridge, Brad, et al. “Attitudes Towards the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Dermatology: A Survey of Australian Dermatologists.” Australasian Journal of Dermatology, vol. 66, no. 5, 2025, pp. e279-e286, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajd.14524.

*Police, Pavithra Reddy, et al. “Diagnostic Accuracy of Artificial Intelligence Dermatology Apps Compared to Clinical Evaluation in Indian Patients With Common Skin Conditions.” International Journal of Research in Dermatology, vol. 11, no. 4, June 2025, pp. 284–90. https://doi.org/10.18203/issn.2455-4529.intjresdermatol20252064.

Trafton, Anne. “Doctors Have More Difficulty Diagnosing Disease When Looking at Images of Darker Skin.” MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 5 Feb. 2024, news.mit.edu/2024/doctors-more-difficulty-diagnosing-diseases-images-darker-skin-0205